This except is from Chapter 14 of SLAG & THE GOLDEN AGE OF LEAD-SILVER ORE and covers my great great grandfather Anton Eilers’ transition from his role as Deputy Commissioner of Mines and Mining Statistics in and West of the Rocky Mountains (under Rossiter Raymond) to Chief Engineer of the Saints John Smelter in 1976, before he moved on to the Germania Smelter in Salt Lake City in September of 1876. Note that while this excerpt includes no footnotes, the book’s version is accompanied by 34 footnotes for this chapter.

CHAPTER 14:

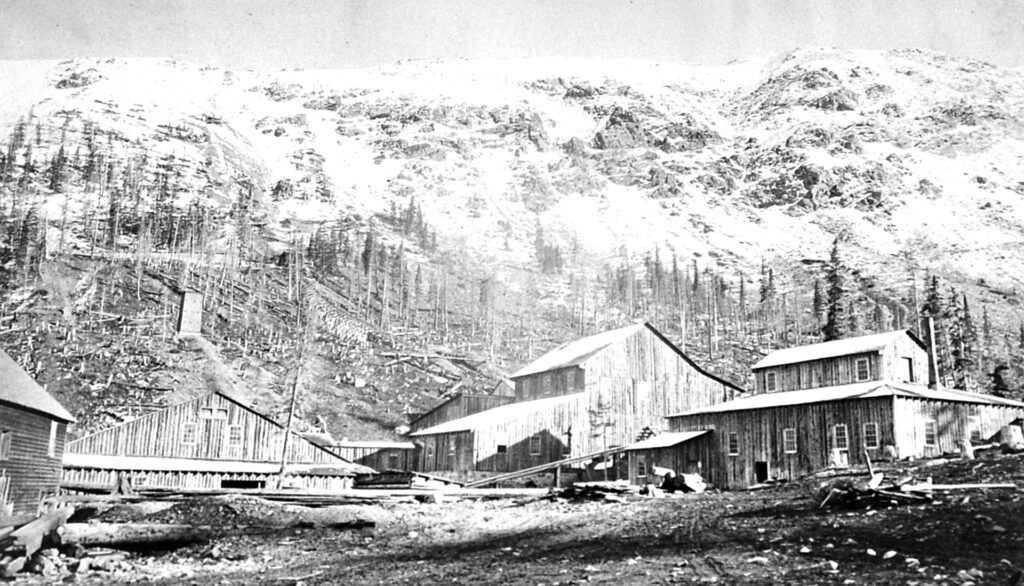

Photo Credit: David Eilers/Family Archives. The Saints John smelter, a couple miles above Montezuma, Colorado, Summer of 1876.

Virtually unknown when he became Raymond’s deputy in 1869, by the end of 1875 thirty-six-year-old Anton Eilers was “the most experienced metallurgist of the day in the lead and copper smelting arena.” Many smelting firms desperately needed his knowledge and skills. One of those companies was the Boston Silver Company. In late 1875, the firm hired him to re-engineer their smelting works in Saints John, Colorado, a far-flung mining camp near the Great Continental Divide that remains a remote place to this day. Despite its location, Anton accepted the offer, giving him a second reason for submitting his resignation as deputy commissioner in early 1876.

Saints John was an offshoot of Colorado’s Pike’s Peak 1859 Gold Rush. Back then, some enterprising prospectors left Cherry Creek to explore the canyon west of Denver City, where today’s Interstate-70 climbs into the Rockies. They settled in an area—now called Georgetown—and panned for gold. In 1863, a man named John Coley hiked south out of Georgetown in search of fortune, eventually finding Colorado’s first silver lode at 12,000 feet, just below Glacier Mountain and the Great Continental Divide. Other prospectors followed Coley’s trail, eventually forming the mining town of Montezuma and, two miles up a nearby canyon, a small mining camp called Coleyville. By 1870, the name Coleyville had been changed to Saints John, named for patron saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist. The Boston Silver Mining Association, which bought the Saints John property in 1870 and opened a mine there, likely influenced the name change. According to one source, the company had a strong Freemason connection, but that hasn’t been verified. Nonetheless, the company operated its works in an unusual fashion. For one thing, it provided a manager’s house furnished with European furniture and a library that contained over 300 books. Though no saloons, bordellos, or gambling was tolerated there, all of that could be found two miles down the hill at Montezuma.

Rossiter Raymond had reported on Saints John in 1869 and 1870 and visited the area, with Eilers, in 1872. By that time, a wide toll road between Georgetown and Montezuma had been built, allowing for the passage of stagecoaches and ore wagons. Anyone who tried to pass without paying faced a $100 fine.

When Raymond published his annual report in 1875, the Boston Silver Mining Association had been reorganized into the Boston Silver Company. In April of that year, Boston’s Comstock mine struck “two feet of solid mineral,” making it potentially one of the richest mines in the territory; however, to realize the strike’s potential, the company’s existing works needed to be rebuilt. Anton probably visited the mine during his final trip west as deputy commissioner and possibly consulted for Boston Silver in late 1875.

In early 1876, Engineer Eilers undertook his new role and drafted a plan for reconstructing the smelter works. Assisting him was Franz Fohr, an experienced mining engineer hired in late 1875 by Boston Mining. Like Eilers, Fohr was a German with mining experience, having immigrated to the United States in 1863. By 1870, he was superintendent of the Newark Smelting & Refining Works in New Jersey, one of only two important lead-silver refineries in the United States, the other being the Thomas Selby plant in San Francisco. In 1874, he went to New York to learn about white lead, then moved to Canada to work silver, before going to Lake Superior to smelt copper. Shortly after that, Boston Silver hired him and he was teamed up with Anton. The pair became fast friends.

In late spring 1876, when the weather warmed enough, Franz Fohr and Anton Eilers, accompanied by Lizzie and their six children, Else (12), Karl (11), Anna (9), Luise (8), Emma (6), and Meta (1), boarded the railroad for the four-day journey to Denver and the territory of Colorado. It was the first time Anton had brought his family west. It was a permanent move, so the family packed many belongings, including Anton’s horse, a Morgan named Vic, in which he took great pride.

At first the children’s excitement was focused on the train itself, but as the hours went by the jostling of the train and familiarity of the passengers grew monotonous. So, the children became fixated on the outside world. As they rolled over Nebraska’s plains, slowly gaining altitude, Anton pointed out the buffalo grass that filled the landscape. He explained that when he first rode the train in 1869, the buffalo had gathered in herds so large, they’d had filled the horizon, all the while feeding on the short, dried up bunches of grass. Millions of them had roamed the prairies. When the herds crossed the railroad tracks, the train’s progress would be halted for a day or more. When the children asked where the buffalo had gone, Anton explained that buffalo hunters had killed millions of them, either for sport or to deprive the Indians of a critical resource.

From the Great Plains of Nebraska the train climbed steadily until the family arrived in the Union Pacific settlement of Cheyenne, where they disembarked. Sitting at 6,000 feet, the flat, dry, and dusty city was once a classic wild-west town where every other business was a saloon. But, once the trains rolled through with regularity, Cheyenne matured quickly. In 1870, the Colorado Central Railroad built a railway connecting Cheyenne to Denver, turning Cheyenne into an important hub. By the time the Eilers family arrived in 1876, the city boasted five thousand residents, and was a cultured city with a robust social life.

The Eilers family, with Fohr’s help, gathered their belongings and transferred onto the train to Denver. As the family traveled south, Lizzie and the children stared west, awestruck by the Rockies and the endless white-capped mountains.

When the train arrived in Denver, Anton couldn’t take his family to Saints John, because there were no accommodations for them there. So, he found a home in Denver at the northeast corner of Lincoln and 16th Avenue. His son Karl Eilers was old enough to remember that the home wasn’t the greatest, as it “was not a very well-built house and had many rodents.” As soon as the family was settled, Anton and Franz left for Montezuma to prepare for the construction of the new smelter.

When Fohr and Eilers arrived at Saints John, they met Boston Mining Company employee Henry Vezin, an “erudite and painstaking” engineer for the company. Vezin was born in 1836 to a large Philadelphia family. Henry’s father had died early, and at the age of twenty-two, Henry lost his mother and two sisters to a ship fire that killed a total of 471 people. He later joined the Union Army and fought bloody battles during the Civil War. After the war, Vezin ventured west and became a mining engineer, eventually landing at Saints John.

Under Anton’s direction, the three men—Eilers, Fohr, and Vezin—managed the construction of the new smelting works. While Vezin was acclimated to life at 12,000 feet, Anton and Fohr often needed to catch their breath. To keep operations going, the trio managed thirty miners, who continued to work Boston Mining’s Comstock mine, while additional hired hands constructed the new smelter and outbuildings. All had to work quickly, because of the short summer season at the high mountain complex. The long days and hard work helped make Eilers, Fohr, and Vezin life-long friends.

Once Anton was certain that construction was on schedule, he returned to Denver to spend some time with his family. When it was time to depart for the mountains again, Anton brought eleven-year-old Karl with him. From Denver, the duo traveled by stagecoach to Georgetown, where they boarded a second coach to Montezuma. There, Karl remembered mounting horses for the two-mile uphill ride to the smelter. He later recalled two things about his visit to Saints John. One was seeing a man ski down a nearby hillside, the first time young Eilers had seen anyone ski. Another memory, a near disaster, resulted from a powerful thunderstorm. As Karl explained it:

The mountains on both sides of the creek were very steep and high, my imagination indicated probably 1000 feet above the valley. During the summer one afternoon we had a tremendous rainstorm, lasting for several hours. Towards evening the rain stopped and the skies were clear. There was a tremendous noise and as we went out in front of the house, we saw a tremendous landslide coming down the side of that one mountain with blocks of rock as large as any of our then houses, rolling before this slide. We all were of course, tremendously thrilled and watched this slide of mud and rock come first down the hill slope and then down along the creek bed. The mud seemed to be at least 10 feet thick and as it rolled on down it came finally to a little wooden bridge across the stream, which of course gave way. We were afraid that this mud might overwhelm the smelter but fortunately after breaking down the bridge it stopped, not a 100 feet from the first of the smelter buildings.

By autumn of 1876, not long after Colorado had finally won statehood, the Saints John works were finished and smelting had begun. Out of the first ten tons of ore, the company yielded silver worth $3,379. Raymond called that a very satisfactory result. Though Anton may have been happy with the new works, he also must have known the location wasn’t suitable for large scale smelting. The altitude, rough terrain, dangerous conditions, and heavy snows meant there were operational limits on the ability to produce substantial silver from the mine. With the new works established and capable men like Fohr and Vezin available to run it, Anton wasn’t needed any longer. Whether he was actively seeking another opportunity or not, another one presented itself.

CHAPTER 14 END

Additional note: Franz Fohr would end up becoming a part of the Eilers family and, after his retirement, spent alternating Sundays with the Eilers family at their homes in Brooklyn and Sea Cliff, New York. After a bout of illness, he passed away at my great grandfather’s (Karl Eilers) home in Sea Cliff in 1919.